-40%

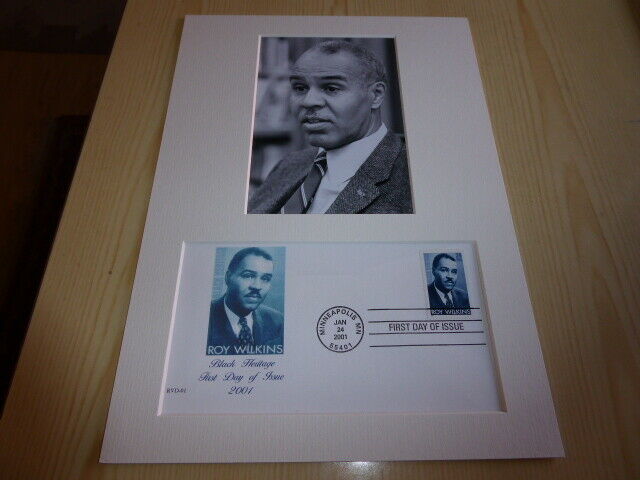

African American Atlanta 1971 Mayor Martin Luther King Sr ! signed first edition

$ 264

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Mayor: Notes on the Sixties by Allen, Ivan With Paul Hemphill New York Simon and Schuster 1971 First Edition Hardcover Very good in very good jacket Hardcover. INSCRIBED and signed by Ivan Allen Jr. (former Mayor of Atlanta) on the front endpaper and inscribed to Martin Luther King Jr's father MLK Sr.To my good friend

Dr Martin Luther King Sr.

with appreciation for his

many acts of friendship

+ support

Sncerely

Ivan Allen Jr.

7/12/71

A very good copy with clean text and tight binding in a very good dust jacket (spine lettering sunned). Protected in a mylar cover.

Civil Rights Activist. He was the prominent pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church for over 40 years, but was most notably known as the father of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.. Known by family and friends as "Daddy King", he was an important civil rights leader in his own right. Few men could be as stubborn and domineering. He lacked intellectual depth and often noted he could be taken to court for his crimes against the English language. Despite suffering great personal insult and loss throughout his life, King, like his son, stuck rigidly to the code of nonviolence and forgiveness. In the 1930s, he built up the membership of Atlanta's Ebenezer Baptist Church to a congregation of several thousand. This gave him a base in the African-American community from where he could preach about civil rights and advocate progressive social action. In 1936, he led the first black voting-rights march in the history of Atlanta. In 1960, he played a key role in mobilizing black support to elect John F. Kennedy president. He also offered crucial support to his son at many times in his career even though they did not always agree. Born Michael King, he was the eldest son of nine children born to poor Georgia sharecroppers, James and Delia King. Growing up in the early part of the twentieth century, he saw firsthand the brutality of southern racism. In his early teens, he was beaten by a white mill owner. He also saw a black man hanged by a white mob. Yet his family continued to advocate nonviolence. When his mother was dying, he cursed white people, but his mother disagreed. "Hatred makes nothin' but more hatred...Don't you do it," she told him. As a member of Floyd Chapel Baptist Church, he was inspired by the few ministers who risked speaking out against racial injustice and decided to become a minister himself. In 1917, despite his educational deficiencies, he was trained and licensed by the ministers from his church. In the spring of 1918, he left Stockbridge to join his older sister Woodie in Atlanta. Woodie was boarding at the home of Rev. A. D. Williams, prominent minister of Ebenezer Baptist Church. King seized the opportunity to introduce himself to the minister's daughter, Alberta Williams. After the two began a courtship, he was quickly welcomed into the Williams household. Rev. and Mrs. Williams supported their future son-in-law's ministerial aspirations by encouraging him to continue his education. He worked a variety of jobs on the railroads, in an auto tire shop, loading bales of cotton, and driving a truck. He also went to school at night, graduating from high school in 1925. He then completed his studies at Bryant Preparatory School and served as pastor of several churches in Atlanta and nearby College Park before becoming assistant pastor of Ebenezer in 1926. He was able to convince the president of Atlanta's Morehouse College that he should be admitted to the three-year minister's degree program at the Morehouse School of religion in 1926 in spite of not fully meeting the school's educational requirements. On Thanksgiving day of that same year, he and Alberta were joined in marriage at Ebenezer. The newlyweds then moved into the Williams family home, where they had three children, Willie Christine, Martin Luther, Jr., and Alfred Daniel, within their first four years of marriage. As he continued his education, he also took over some of the duties at the church. When his father-in-law suddenly died in the spring of 1931, he was voted pastor. Through membership and fundraising drives, he rescued the church from financial ruin brought by the Great Depression and preached his message of social action and nonviolence. In the 1930s, King joined the NAACP, the Atlanta Negro Voters League, and the Interracial Council of Atlanta. In addition to the voting-rights march, he worked at integrating the Ford Motor Company and ending segregation of the elevators in the Fulton County courthouse. By 1934, he was a well-respected pastor and traveled to the World Baptist Alliance in Berlin. Also at this time, he changed his name and that of his oldest son to Martin Luther King at the wish of his dying grandfather. Never hesitating to direct his influence as a pastor toward the cause of racial equality, he headed Atlanta's Civic and Political League and NAACP branch. But perhaps his most significant contribution to the civil rights movement was the influence he had on the development of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s social consciousness. From 1956 to 1968 his son rose to be one of the major national leaders of the civil rights movement and throughout his son's career, he continued to advocate racial equality within his church and community. April of 1968 began a series of tragedies in the life of King with the assassination of his son which devastated him. Upon seeing his son's body in the casket, he was more a father trying to wake his son from a nap finally collapsing and sobbing. "He never hated anybody," the old man softly cried. "He never hated anybody." In 1969 his younger son A. D. drowned in a mysterious swimming pool accident and in 1974 his beloved wife who he called "Bunch" was shot while playing the organ at Ebenezer (The assassin later admitted that King had been his target). In spite of the spiritual strength provided by the Lord, he grieved deeply. He stepped into a public role after his son's death, attending events that honored his son and delivering the invocation at the 1976 and 1980 Democratic National Conventions. He continued to preach at Ebenezer until his resignation in 1975. In the fall of that same year he becomes the first African-American to address a joint session of the Alabama state legislature. In 1976, when presidential candidate Jimmy Carter made a remark about "ethnic purity," many believed that would lose him the southern black vote. King played an instrumental role in preventing that. When King hugged Carter on a public platform, it symbolized Carter's acceptance by black civil rights leaders, and Carter went on to win 90 percent of the black vote. In August 1976, King found himself in a coronary care unit. The following year he was treated for congestive heart failure. Although his steps were slowing, and he needed a cane to use for balance, his spirit still sought usefulness and service. He spent the remainder of his life giving lectures and as a guest minister at churches. On the morning of November 11, 1984, he attended services at Atlanta's Salem Baptist Church. That afternoon, he suffered a heart attack and was rushed to Crawford W. Long Memorial Hospital and died that afternoon at 5:41 p.m. with his surviving child and a grandson at his side. Days later on November 16, 1984, nearly 3,000 blacks and whites stood side by side at his funeral at Ebenezer Baptist Church. One by one, leaders of the nation came to offer memories of and tributes to the man who had occupied the church's pulpit for 44 years and whose faith in God and compassion for his fellow man directed his life.

In a speech expressing his views on ‘‘the true mission of the Church’’ Martin Luther King, Sr. told his fellow clergymen that they must not forget the words of God: ‘‘The spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the Gospel to the poor.… In this we find we are to do something about the brokenhearted, poor, unemployed, the captive, the blind, and the bruised’’ (King, Sr., 17 October 1940). Martin Luther King, Jr. credited his father with influencing his decision to join the ministry, saying: ‘‘He set forth a noble example that I didn’t [mind] following’’ (Papers 1:363).

‘‘Rev. King Is Royally Welcomed on Return From Europe,’’ Atlanta Daily World, 28 August 1934.King, Sr., with Riley, Daddy King, 1980. King, Sr., ‘‘Moderator’s Annual Address,’’ 17 October 1940, CSKC. King, Stride Toward Freedom, 1958. King, ‘‘An Autobiography of Religious Development,’’ 12 September–22 November 1950, in Papers 1:359–363. Introduction in Papers 3:14.SOURCES Throughout his life, King, Sr. was a prominent civic leader in Atlanta, serving on the boards of Atlanta University, Morehouse College, and the National Baptist Convention. After the assassination of King, Jr., he spoke at numerous events honoring his son. A strong supporter of Jimmy Carter, he delivered invocations to the Democratic National Convention in 1976 and 1980. After serving Ebenezer for 44 years, he died in Atlanta in 1984.King, Sr. was generally supportive of his son’s participation in the civil rights movement; however, during the Montgomery bus boycott, he and his wife were very concerned about the safety of King, Jr. and his family. King, Sr. asked a number of prominent Atlantans, such as Benjamin Mays, to try to convince King, Jr. not to return to Montgomery; but they were unsuccessful. King, Sr. later wrote, ‘‘I could only be deeply impressed with his determination. There was no hesitancy for him in this journey’’ (King, Sr., 172). King, Sr. traveled with the delegation to Oslo in 1964 to see his son accept the Nobel Peace Prize. In his autobiography, King, Sr. recalled, ‘‘As M. L. stood receiving the Nobel Prize, and the tears just streamed down my face, I gave thanks that out of that tiny Georgia town I’d been spared to see this and so much else’’ (King, Sr., 183). Although too young to fully understand his father’s activism, King, Jr. later wrote that dinner discussions in the King household often touched on political matters, as King, Sr. expressed his views about ‘‘the ridiculous nature of segregation in the South’’ (Papers 1:33). King, Jr. remembered witnessing his father standing up to a policeman who stopped the elder King for a traffic violation and referred to him as a ‘‘boy.’’ According to King, Jr., his indignant father responded by pointing to his son and asserting: ‘‘This is a boy. I’m a man, and until you call me one, I will not listen to you.’’ The shocked policeman ‘‘wrote the ticket up nervously, and left the scene as quickly as possible’’ (King, Stride, 20). In Atlanta, King, Sr. not only engaged in personal acts of political dissent, such as riding the ‘‘whites only’’ City Hall elevator to reach the voter registrar’s office, but was also a local leader of organizations such as the Atlanta Civic and Political League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1939, he proposed, to the unopposition to more cautious clergy and lay leaders, a massive voter registration drive to be initiated by a march to City Hall. At a rally at Ebenezer of more than 1,000 activists, King referred to his own past and urged black people toward greater militancy. ‘‘I ain’t gonna plow no more mules,’’ he shouted. ‘‘I’ll never step off the road again to let white folks pass’’ (King, Sr., 100). A year later, King, Sr. braved racist threats when he became chairman of the Committee on the Equalization of Teachers’ Salaries, which was organized to protest discriminatory policies in teachers’ pay. With the legal assistance of the NAACP, the movement resulted in significant gains for black teachers. In 1934, King, Sr. attended the World Baptist Alliance in Berlin. Traveling by ocean liner to France, he and 10 other ministers also toured historic sites in Palestine and the Holy Land. ‘‘In Jerusalem, when I saw with my own eyes the places where Jesus had lived and taught, a life spent in the ministry seemed to me even more compelling,’’ King recalled (King, Sr., 97). A story appearing in the Atlanta Daily World upon King’s return to Atlanta in August 1934 increased his prominence and relative affluence among Atlanta’s elite. This was also reflected in the final transformation of his name from Michael King to Michael Luther King and finally Martin Luther King (although close friends and relatives continued to refer to him and his son as Mike or M. L.). The Kings raised their children in what King, Jr. described as ‘‘a very congenial home situation,’’ with parents who ‘‘always lived together very intimately’’ (Papers 1:360). Hidden from view were his parents’ negotiations regarding their conflicting views on discipline. Although King, Sr. believed that the ‘‘switch was usually quicker and more persuasive’’ in disciplining his boys, he increasingly deferred to his wife’s less stern but effective approach to childrearing (King, Sr., 130). After the death of A. D. Williams in 1931, King, Sr. succeeded his father-in-law as pastor of Ebenezer. According to King’s recollections, A. D. Williams inspired him in many ways. Both men preached a social gospel Christianity that combined a belief in personal salvation with the need to apply the teachings of Jesus to the daily problems of their black congregations. On Thanksgiving Day 1926, Michael Luther King and Alberta Christine Williams were married at Ebenezer. The newlyweds moved into an upstairs bedroom of the Williams’ house on Auburn Avenue. The King family quickly expanded, with the birth of Willie Christine in 1927, Michael Luther, Jr. in 1929, and Alfred Daniel Williams in 1930, a month after King, Sr. received his bachelor’s degree in Theology. In March 1924, the engagement of Alberta to Michael King was announced at Ebenezer’s Sunday services. Meanwhile, King served as pastor of several churches in nearby College Park, while studying at Bryant Preparatory School. He followed the urging of Alberta Williams and her father to seek admission to Morehouse College and was admitted in 1926. King found the work difficult; however, he relied on the help of classmate Melvin H. Watson, the son of a longtime clerk at Ebenezer Baptist Church, and Sandy Ray of Texas, a fellow seminarian. ‘‘We shared an awe of city life, of cars, of the mysteries of college scholarship, and, most of all, of our callings to the ministry,’’ King recalled (King, Sr., 77). In the spring of 1918, King left Stockbridge to join his sister, Woodie, in Atlanta. The following year, Woodie King boarded at the home of A. D. Williams, minister of Ebenezer Baptist Church. King seized the opportunity to introduce himself to the minister’s daughter, Alberta Williams. Her parents welcomed King into the family circle, eventually treating him as a son and encouraging the young minister to overcome his educational limitations. King experienced a number of brutal incidents while growing up in the rural South, including witnessing the lynching of a black man. On another occasion he had to subdue his drunken father who was assaulting his mother. His mother took the children to Floyd Chapel Baptist Church to ‘‘ease the harsh tone of farm life’’ according to King (King, Sr., 26). Michael grew to respect the few black preachers who were willing to speak out against racial injustices, despite the risk of violent white retaliation. He gradually developed an interest in preaching, initially practicing eulogies on the family’s chickens. By the end of 1917, he had decided to become a minister. King, Sr. was born Michael King on 19 December 1897, in Stockbridge, Georgia. The eldest son of James and Delia King, King, Sr. attended school from three to five months a year at the Stockbridge Colored School. ‘‘We had no books, no materials to write with, and no blackboard,’’ he wrote, ‘‘But I loved going’’ (King, Sr., 37). Martin Luther King, Sr. (born Michael King; December 19, 1899 – November 11, 1984), was an American Baptist pastor, missionary, and an early figure in the American Civil Rights Movement. He was the father of Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr.

Contents [hide]

1 Early life

2 Ebenezer Baptist Church

3 Murder of wife

4 Later life

5 Death

6 Books

7 Movies and television

8 See also

9 References

Early life[edit]

King was born Michael King in Stockbridge, Georgia, the son of Delia (née Linsey) and James Albert King.[1] He led the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, and became a leader of the Civil Rights Movement, as the head of the NAACP chapter in Atlanta and of the Civic and Political League. He encouraged his son to become active in the movement.

Ebenezer Baptist Church[edit]

King was a member of the Baptist Church and decided to become a preacher after being inspired by ministers who were prepared to stand up for racial equality. He left Stockbridge for Atlanta, where his sister Woodie was boarding with Reverend A.D. Williams, then pastor of the First Baptist Church (Atlanta, Georgia). He attended Dillard University for a two-year degree. After King started courting Williams' daughter, Alberta, her family encouraged him to finish his education and to become a preacher. King completed his high school education at Bryant Preparatory School, and began to preach in several black churches in Atlanta.

In 1926, King started his ministerial degree at the Morehouse School of Religion. On Thanksgiving Day in 1926, after eight years of courtship, he married Alberta in the Ebenezer Church. The couple had three children in four years: a daughter, Willie Christine King (born 1927), Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr., 1929–1968), and a second son, Alfred Daniel Williams King (1930–1969).

King became leader of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in March 1931 after the death of Williams. With the country in the midst of the Great Depression, church finances were struggling, but King organized membership and fundraising drives that restored these to health. By 1934, King had become a widely respected leader of the local church. That year, he also changed his name (and that of his eldest son) from Michael King to Martin Luther King after becoming inspired during a trip to Germany by the life of Martin Luther (1483–1546), the German theologian who initiated the Protestant Reformation (though he never changed his name legally).[2][unreliable source?]

King was the pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church for four decades, wielding great influence in the black community and earning some degree of respect from the white community. He also broadcast on WAEC, a religious radio station in Atlanta.

In his 1950 essay An Autobiography of Religious Development, King Jr. wrote that his father was a major influence on his entering the ministry. He said, "I guess the influence of my father also had a great deal to do with my going in the ministry. This is not to say that he ever spoke to me in terms of being a minister, but that my admiration for him was the great moving factor; He set forth a noble example that I didn't mind following."

King Jr. often recounted that his father frequently sent him to work in the fields. He said that in this way he would gain a healthier respect for his forefathers.

In his autobiography, King Jr. remembered his father leaving a shoe shop because he and his son were asked to change seats. He said, "This was the first time I had seen Dad so furious. That experience revealed to me at a very early age that my father had not adjusted to the system, and he played a great part in shaping my conscience. I still remember walking down the street beside him as he muttered, 'I don't care how long I have to live with this system, I will never accept it.'"[3]

Another story related by King Jr. was that once the car his father was driving was stopped by a police officer, and the officer addressed the senior King as "boy". King pointed to his son, saying, "This is a boy, I'm a man; until you call me one, I will not listen to you."

King Jr. became an associate pastor at Ebenezer in 1948, and his father wrote a letter of recommendation for him to Crozer Theological Seminary. Despite theological differences, father and son would later serve together as joint pastors at the church.

King was a major figure in the Civil Rights Movement in Georgia, where he rose to become the head of the NAACP in Atlanta and the Civic and Political League. He led the fight for equal teachers' salaries in Atlanta. He also played an instrumental role in ending Jim Crow laws in the state. King had refused to ride on Atlanta's bus system since the 1920s after a vicious attack on black passengers with no action against those responsible. King stressed the need for an educated, politically active black ministry.

In October 1960, when King Jr., was arrested at a peaceful sit-in in Atlanta, Robert Kennedy telephoned the judge and helped secure his release. Although King Sr. had previously opposed Kennedy because he was a Catholic,[citation needed] he expressed his appreciation for these calls and switched his support to Kennedy. At this time, King had been a lifelong registered Republican, and had endorsed Republican Richard Nixon.[citation needed]

King Jr. soon became a popular civil rights activist. Taking inspiration from Mohandas Gandhi of India, he led nonviolent protests in order to win greater rights for African Americans.

King Jr. was shot and killed in 1968. King Sr.'s youngest son, Alfred Daniel Williams King, died of an accidental drowning on July 21, 1969, nine days before his 39th birthday.

In 1969, King was one of several members of the Morehouse College board of trustees held hostage on the campus by a group of students demanding reform in the school’s curriculum and governance. One of the students was Samuel L. Jackson, who was suspended for his actions. Jackson subsequently became an actor and Academy Award nominee.[4]

King played a notable role in the nomination of Jimmy Carter as the Democratic candidate for President in the 1976 election. After Carter's success in the Iowa caucus, the New Hampshire primary and the Florida primary, some liberal Democrats were worried about his success and began an "ABC" ("Anyone But Carter") movement to try to head off his nomination. King pointed to Carter's leadership in ending the era of segregation in Georgia, and helping to repeal laws restricting voting which especially disenfranchised African Americans. With King's support, Carter continued to build a coalition of black and white voters and win the nomination. King delivered the invocation at the 1976 and 1980 Democratic National Conventions. King was also a member of Omega Psi Phi.

Murder of wife[edit]

King Sr.'s wife and King Jr.'s mother, Alberta, was murdered on Sunday, June 30, 1974 at the Ebenezer Baptist Church during Sunday services by Marcus Wayne Chenault. He was a black man from Ohio who stood up and yelled, "You are serving a false God", and began to fire from two pistols while Alberta was playing "The Lord's Prayer" on the church organ.[5] Upon capture, the assassin disclosed that his intended target was Martin Luther King Sr., who was elsewhere that Sunday. After failing to see Mr. King Sr., the killer instead fatally shot Alberta King and Rev. Edward Boykin.[6] Chenault stated that he was driven to murder after concluding that "black ministers were a menace to black people" and that "all Christians are my enemies".[7]

Later life[edit]

With his son's widow Coretta Scott King, King was present when President Carter awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom to King Jr. posthumously in 1977.

King published his autobiography in 1980.

Death[edit]

King died of a heart attack at the Crawford W. Long Hospital in Atlanta on November 11, 1984, at age 84. He was interred next to his wife Alberta at the South View Cemetery in Atlanta.[8]

Books[edit]

David Collins (1986) Not Only Dreamers: the story of Martin Luther King, Sr. and Martin Luther King, Jr. (Elgin, Ill: Brethren Press) ISBN 978-0-8717-8612-8

Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr. (1980) Daddy King: an Autobiography (New York: William Morrow & Co.) ISBN 978-0-6880-3699-7

Mary-Anne Coupell (1985) Martin Luther King Jr.'s Whole Life, (Beijing: Brethren Press)

Murray M. Silver, Esq. (2009) Daddy King and Me; Memories of the Forgotten Father of the Civil Rights Movement, (Savannah, Ga., Continental Shelf Publishers) ISBN 978-0-9822-5832-3

Movies and television[edit]

Poster for the 2016 documentary film In the Hour of Chaos.

In the Hour of Chaos is a 2016 American documentary drama written and directed by Bayer Mack (The Czar of Black Hollywood), which tells the story of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr.'s rise from an impoverished childhood in the violent backwoods of Georgia to become patriarch of one of the most famous – and tragedy-plagued – families in history.[9]

From The Huffington Post:

"The documentary weaves strands of three stories into one. The underpinnings of the documentary are the events of the time — everything from the Atlanta Riots and the disenfranchisement of blacks throughout the South to the era of prohibition and war time. Over this background, there are two more stories — that of Daddy King and the story of Daddy’s influence on Martin Jr."[10]

Part one of In the Hour of Chaos aired on public television in early 2016 and the full film was released online July 1, 2016.[11][12]